8

A Note on the AA Files Display Initials

One-off Three: all styles

8.1

Gruppo 9999 performing ‘Standing Spaces’ at Space Electronic, c. 1970

First published in 1981, AA Files is the Architectural Association School of Architecture’s journal of record and the successor to a long line of house journals that began with the school’s founding in the mid-nineteenth century. Published twice a year and featuring essays and conversations on all aspects of architectural history, practice and criticism, its current guise — easily recognisable by its spectrum of monochrome covers — is edited by Thomas Weaver and was redesigned by John Morgan studio in 2008, a collaboration announced with the bright yellow cover of AA Files 57. This particular issue introduced a number of editorial and design changes, one of which was the first appearance of display initials integrated into a limited number of essays within each issue — a form of typographic vernacular that seemed very much in keeping with the shifting styles that have defined the AA School and more generally architecture’s enduring relationship with language.

Of course, ‘English vernacular’ is its own style of letterform. The term itself was coined by James Mosley (while librarian at London’s St Bride Library) to categorise the eighteenth- and nineteenth-centuries display types developed in England to meet the new demands of commerce, print and inscription. The originality of these letter faces lay in their adaptability to the variants of Egyptian, Tuscan and Grotesque forms while sharing a common design language, and which in many cases originated with signwriters and architects. However, its development was interrupted by the broad-pen lettering of Edward Johnston’s Writing & Illuminating & Lettering manual of 1906 and the establishment of the ‘Trajan norm’, which in turn prompted often rather dull, stereotyped letterforms, and the subsequent demise of the English vernacular in public lettering and type founding.

The idea behind the introduction of display types in AA Files was to reactivate the English vernacular model, not by producing pastiche historical type families, but rather by continuing to explore the once vital variations on this theme. In this, the studio initially worked closely with Paul Barnes on the first issues, starting with a Caslon sans and a shadowed reversed-contrast Italian reproduced in a warm typographic red in issue 57. My own relationship with the John Morgan studio began in 2011, after the completion of an MA in type design at the University of Reading. AA Files 63 was one of the first projects I worked on. By then the studio had solicited quite a lot of lettering from Paul and so we were keen on being more hands-on with the design of our letters. It was therefore decided that in addition to typesetting the journal I would also draw the display initials for each issue.

y first letterforms — an A, M and W — were a contemporary reworking of the nineteenthcentury poster types by Louis John Pouchée (1782–1845). A French émigré, working in London’s Lincoln’s Inn Fields, Pouchée’s signature series of finely crafted decorative alphabets were typically in a nineteenth-century fat face adorned with images of fruit and vegetables, farm animals, agricultural workers and various Masonic symbols. I responded to an essay on Finnish architect Alvar Aalto by filling our Pouchées with characteristic emblems of Finland — from Moomin and Nokia to Aalto’s furniture and fabric patterns by Marimekko — drawn late at night and assisted by numerous online image search results. The letters themselves are a fat version of an English Egyptian — a typeface I was working on at the time, based on William Caslon’s sans serif of 1816 — with an added shadow, and whose wide profile allowed for a generous amount of filling.

Our own Pouchées also established a working model we have since reproduced with each issue, not least that these initials are often drawn late in the process of designing the journal, very close to print deadlines. This means that their choice and character is somehow both spontaneous and pragmatic. Their frequency and appearance is also very much defined by how much space I can afford to play with — in AA Files we try to avoid white space in text as much as possible, making use of images and typesetting tricks to ensure that (almost) every piece ends on the very bottom of its last page. This means that a certain amount of custom editing is required. But even more text manipulations are demanded by the display initials — rewriting opening sentences to correspond with the specific letters that we like, or have time to design.

In a way, this small shift — custom designing letters to fit the variances of specific content — meant that although the displays are still vernacular in nature, they also happen to reference other times and places. And so what began as a resolutely English vernacular tradition has since moved from the shores of England onto a small tour of Europe’s typographic landscape.

he distinctly French character of the next batch of letters (a direction for which, I must say, I am not fully responsible) persisted in the letters drawn for AA Files 64. Here they directly reference the typography of the front cover of the 1964 Delpire edition of La Tour Eiffel, from which an essay by Roland Barthes has been reproduced in AA Files in a new English translation. The model I used, suitably named ‘French Antique’, is from a 1865 specimen of the Scottish type foundry Miller & Richard. I drew the letters A, F, O, S and T based on the specimen at hand, quite faithfully at first, but then condensed them to further reference the exaggerated horizontal and weak vertical strokes of the woodblock faces used in Massin’s design for Jean Cocteau’s Les Mariés de la tour Eiffel (1948). Producing a towering, narrow letter also seemed especially apposite given the subject matter.

Remaining, rhetorically speaking, in Paris, further French-styled letters followed our Pouchée re-enactments in offering something really quite decorative.

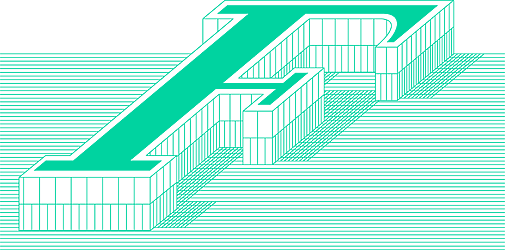

or example, the display initials for issue 68 are a reconstruction of a letter face illustrated by Joseph-Balthazar Silvestre (1791–1869), a French paleographer, calligrapher and miniature painter. In 1843 Silvestre published his Alphabet-Album, a collection of 60 alphabet plates engraved by François Girault, drawn from Europe’s grandest libraries or specifically designed by Silvestre. Our own reclining F and T appeared to be an especially good fit for the piece by Marie-Antoine Carême, a late-eighteenth-century chef and contemporary of Silvestre. Carême had a passion for architecture, drawing building models as plans for his pièces montées, a synthesis which is nicely mirrored in the layered and axonometric qualities of these letters.

old Schwarzenegger — whose passion for architecture skews towards that of the body-building variety — opened a text by Sam Jacob in AA Files 70, on the subject of the Vitruvian Man. In contrast to issue 68, the letters here feature a more illustrative kind of decoration. It seemed like an opportunity too good to pass up to adapt Geoffroy Tory’s Champ Fleury of 1529 — appropriately subtitled The Art and Science of the Proportion of the Attic or Ancient Roman Letters, According to the Human Body and Face. I recycled Tory’s lettering and then substituted the face and body in his drawings for Sam’s. These were especially challenging to draw, not because of the letters — which are actually not that interesting — but because of the portraiture work they involved and my nervousness about how Sam might react to them (he loved them, which was a relief). I drew faces, bodies, grids and letters for A, C, I, K, M, O, S and a three-dimensional ARN cube which we managed to fit in with some creative editing.

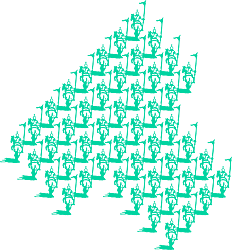

his symbolically Renaissance idea of harmonic perfection had later echoes in the more explicitly Italianate letterforms we developed in subsequent issues. For instance, in issue 73 I played with modular lettering made up of cavalry figures in the style of the celebrated Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio’s illustrated edition of Polybius’ Histories, which he worked on in the years immediately before his death in 1580. The Histories itself was written c. 140BC and offers an account of various Roman campaigns, including the defeat of Hannibal and the destruction of Carthage. I borrowed a Roman eques (cavalryman) and his mount from Palladio’s detailed drawings of battle formations and replicated these formations in the shape of letters — B, G, P and T — rendered, like Palladio’s, with the minutiae of every helmet, lance, hoof and swishing tail.

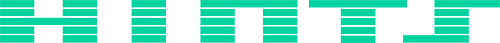

ot all of the journal’s lettering advertises such an extended history. And so for issue 69 — in particular a new translation of Michel Foucault’s famous ‘Heterotopias’ essay — the letters reference the disco aesthetic of the Italian radical movement, described in another essay in the same issue on the avant-garde collective Gruppo 9999. I drew very basic letterforms (for the letters A, B, F, H, I, N, S, T and W), whose characteristic square and circle shapes can also be traced back to 1920s experiments. ‘The letter which we place before you does not pretend to substitute the forms of the past’, announced the Deberny & Peignot specimen for A.M. Cassandre’s Bifur, ‘it simply marks the crossroads which it may be well to explore’. These letters do not reference anything in particular, and instead draw on numerous Bauhaus posters and paintings — from Kandinsky’s colours and shapes to Hannes Meyer’s images of the Neue Welt — but ultimately their true home is in the subterranean discos of 1970s Florence.

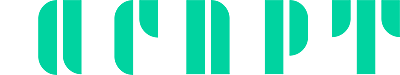

similar period — and style — is explored in issue 66, with the reconstruction of two alphabets developed by architect Carlo Scarpa between 1969 and 1978 for the Brion family tomb in San Vito di Altivole, Treviso (Scarpa talked of his ‘calligraphy’ as having been ‘invented many times before’, referencing the kind of modular letterforms to which he was especially drawn).

or the original version of the lowercase alphabet (for which I drew b, f, i, o, r and t) Scarpa constructed a tubular lead lettering, while the horizontal slats of the uppercase version (a, h, i, n, s and t) were made of ivory inlaid into ebony. Scarpa’s typographic work is fascinating, not only for the quality of his letters but also their elegant integration into the various materials he set them. As a result, I spent a lot of time looking at his work, but mostly for the sheer pleasure of it.

idely known among architecture’s crossover with typography are the geometric letterforms designed by Josef Albers, and his stencil types, which he developed in the early 1920s while teaching at the Bauhaus in Weimar, appear in a text he authored in issue 67. In his short essay, ‘Regarding the Economy of Typeface’ (1926), Albers wrote somewhat modestly that his stencil alphabet — of which I drew the uppercase letters A, C, N, P, T and W — did not claim to be definitive, and was designed only to solicit interest and collaboration from his colleagues. He apparently succeeded in this ambition, as the geometric rationality of Albers’ design definitely influenced the letters I produced for earlier issues.

t also appeared most recently in my display initial for AA Files 74. Here the single display letter derives from a logotype that the historian and architect Joseph Rykwert produced as part of his commission to design the short-lived Wips nightclub in London’s Leicester Square — a design that shares certain similarities with the work of the artist and typographer Edward Wright, a close friend of Rykwert’s. At Wips, Rykwert etched his striated logo into the club’s entrance sign as well as its glass ashtrays. The density of the page meant that in the end I only had room for one letter — a lowercase i — which I extracted from an incredibly precise technical drawing that Rykwert produced at the time, drawing the four letters of the club’s name with all of the precision of an architectural plan.

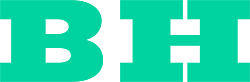

ounding out a tour of Europe and its architectural cultures, we then came full circle in issue 72 with a return to the English vernacular model. The display featured in essays on and by Colin Rowe are an adaptation of two slab serif typefaces developed in the first half of the nineteenth century by the English punchcutters Bower & Bacon and by the Fann Street Foundry, bought in 1820 by William Thorowgood with a large sum of money he had just won in the lottery (besides his good luck, Thorowgood will be also remembered as the first to use the term ‘grotesque’ to describe a sans serif). Similar alphabets were used in the 1940s in the pages of The Architectural Review — a journal that first published Rowe’s essay, ‘The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa’ in March 1947 — whose characteristically English vernacular typography also seems fitting given Rowe’s idiosyncratic, spoken and resolutely English prose.

or the first alphabet I drew disproportionately outlined A, I, R and S, while the second (B, F and H) is a very straightforward slab serif, but more than made up for its lack of features by being reproduced at huge scale across several columns of text — nineteenth-century letterforms as late-twentieth-century supergraphics.

And so what might come next? Might this northern European focus be interrupted by references drawn from other architectural and typographic cultures, for example by Latin American modernism, or even by Japanese traditionalism? Might their forms be abstract or representative, intellectual or populist? Really, I have no idea, but over an evening or two in late November I will have to have resolved these things, if only because a day or two later the issue will go to press.

8.2

Pouchée, issue 63, 2011

8.3

French Antique, issue 64, 2012

8.4

Silvestre, issue 68, 2014

8.5

Champ Fleury, issue 70, 2015

8.6

Histories, issue 73, 2016

8.7

Disco, issue 69, 2014

8.8

Brion Ivory, issue 66, 2013

8.9

Brion Lead, issue 66, 2013

8.10

Albers, issue 67, 2013

8.11

Five-Line White, issue 72, 2016

8.12

Six Lines Pica Egyptian, issue 72, 2016

colour

AA Files is printed in CMYK and two spot colours. The first is used on the cover and the second on the first and last two pages. The display initials are usually printed in this second colour, which can sometimes be a reference to a piece of writing or image from the journal, or simply to some passing seasonal taste. Here, they are reproduced in the industrial green chosen for Footnotes’ second issue.

context

AA Files

Edited by Thomas Weaver

297 × 245 mm, paperback, 160–200 pp. (recent issues)

Published twice a year by the Architectural Association, London

Designed by John Morgan studio

biography

Adrien Vasquez (*1986) is a French typographer and type designer working with John Morgan in London. Together they set up ABYME, a digital type foundry and publisher, which will launch later this year. He has contributed to the journals .txt, Azimuts and From–To, and recently co-edited with Wayne Daly Dressed in Black, a research on the design work of book designer Lothar Reher, published by Precinct.

acknowledgements

Thanks to John Morgan, Thomas Weaver and Sarah Handelman at the Architectural Association, and Rudy Geeraerts at Ourtype

further reading

Nicolete Gray, Nineteenth Century Ornamented Typefaces (London: Faber and Faber, 1976)

John Morgan, ‘A Note on the Type’, AA Files 57 (London: Architectural Association, 2008), p. 84

James Mosley, ‘English Vernacular: A Study in Traditional Letter Forms’, Motif 11 (1963), pp. 3–55

James Mosley, ‘Naming Victory: In Search of an English Vernacular Letter’, AA Files 60 (London: Architectural Association, 2010), pp. 56–65

iconography credits

8.1 Giorgio Birelli © Gruppo 9999

iconotrack

Catharine Rossi, Lucia Galli, Terry Fiumi

notes

This piece does not include the display initials from AA Files 65, for which we used our Nizioleti typeface, a reconstruction of Venice’s street sign lettering originally drawn for the identity of the 2012 Venice Architecture Biennial. It also omits the geometric numbers drawn for AA Files 71, which took its cues from the lettering of a temporary shopfront designed by architect Gabriel Guevrekian for the Simultané fashion line of Sonia Delaunay and Jacques Heim, as part of the 1925 Exposition des Arts Décoratifs in Paris.

online version info

Originally published in issue B, 2017.